Forensic Accounting: Tax in Matrimonial Matters

It goes without saying that a couple’s decision to separate or file for divorce brings with it significant emotional and practical upheaval both for one another, but also for any family and children that it directly affects.

Amid the challenges that come during this period, sometimes that last thing that either party wants to think about is the financial issues and considerations that accompany the end of a marriage. High among these considerations is the impact of tax on the divorce and any eventual settlement. Tax is a vital component of the proceedings and with proper consideration regarding the timing of the divorce, tax residency and domicile, treatment of each spouse’s assets and with appropriate planning, both parties potentially can minimise the tax arising from transfers occurring under the divorce settlement. We recently hosted a UK200 Group webinar on Tax in Matrimonial Matters and in this article we recap some of the key points discussed during that webinar.

It is first useful to note that one of the most important practical implications from both a legal and tax perspective in divorce settlements is the stages of divorce, and when they occur in relation to the tax year end (5th April).

The three key stages of divorce here are:

- Separation – perhaps self-explanatory, this is the point at which the couple decide to separate. If a divorce, rather than an informal separation, is sought then typically one spouse seeks a divorce and will file a matrimonial order (previously known as a divorce petition). However, from April 2022 the law on divorce is due to change as no fault divorce comes in and couples will be able to file jointly for a divorce.

- Decree Nisi – the Decree Nisi is a conditional decree of divorce which, in simple terms, means that the court is satisfied that the legal and procedural requirements to attain a divorce have been met. At this point the marriage still exists and the applicant must wait 6 weeks and 1 day before applying for the Decree Absolute.

- Decree Absolute – this is the final decree and legally ends the marriage.

While there are other stages in the divorce proceedings with legal significance, these particular stages are important for the purposes of tax, as we will come on to discuss.

Tax implications in divorce

The two main taxes that need to be considered in divorce proceedings are Income and Capital Gains tax.

Income tax

Spouses are treated as separate individuals from an income tax perspective, therefore there does not tend to be many implications within divorce proceedings. However, a few key things note are:

- Maintenance payments – Often we come up against the question of the treatment of any maintenance payments. In the UK, maintenance payments do not generate an income tax liability, nor do they provide any reliefs through income tax deduction. However, this can differ in other jurisdictions, (i.e., the US), therefore if one of the parties is not a UK domicile or resident for tax purposes, then this may require further investigation and advice.

- Investment properties – A key thing to note with investment properties and any income realised from them during a divorce is the spouse who receives the property must now include that property within their self-assessment return. The receiving spouse may or may not have ever been in the UK self-assessment tax system before and therefore may be unfamiliar with HMRC’s requirement and processes, particularly regarding filing and payment dates which can be very daunting. If this is you, it is worth consulting with an accountant or tax advisor who will be able to support you with filings both during the divorce settlement and on an ongoing basis.

Capital Gains Tax

Capital Gains Tax (CGT) is a more complex issue with regard to transfers in divorce proceedings, and if not planned for appropriately can incur a considerable CGT liability. This is really where the stages of divorce and timing of transfers interact and can make a significant difference to the tax payable.

In normal marital circumstances (there is no planned separation/ divorce) a married couple can transfer assets at No Gain No Loss (NGNL) which means that the recipient of the assets will receive them at the original market value i.e., any embedded gains move with the asset and there is no CGT due. The recipient (or original holder, if no transfers take place) pays CGT on any profits in the future on disposal of the asset at a rate of 10% (or 20% for higher rate Income Tax payers) for all chargeable assets, excluding residential property which is charged at 18% (or 28% for higher rate Income Tax payers). UK resident individuals usually receive an annual exemptions amount against their CGT liability on the asset(s) which is typically calculated by deducting the inherited/purchased cost from the current market value at transfer; however, this is not transferrable between spouses.

In circumstances of divorce, CGT is not as straightforward.

- If the divorce settlement completes (decree absolute) in the same tax year of separation then the NGNL rule still applies. However, in reality, divorces are more than just about the financial and tax settlements and many settlements take far longer than a year to complete.

- Therefore, if the divorce process spans into the subsequent tax year of separation then the spouses become treated as connected persons up to the point of decree absolute and any disposals, transfers or gifts will be seen as a deemed disposal for CGT at market value, which will trigger a liability either as capital gain or capital loss.

- After the decree absolute, spouses are no longer connected and, therefore, transfer will be a disposal at market value if it’s not an arm’s length transaction. It is only not an arm’s length transaction if the recipient paid market value for the asset. CGT is then due on any gain.

The date of the transfer/ disposal in terms of which tax year it took place in is clearly very important, as is illustrate below. However, the precise date of transfer is also important if UK property or land is involved because the UK now has an extra binding requirement for any capital returns from transfers of that nature.

In addition, the nature of the transfer is important. Usually, if the transfer was a gift then the date that those assets were gifted is known and it’s fairly straight forward. However, if the transfer is under a court order then the date will be one of three time points:

1. If the assets transfer under a court order before decree absolute, then the date of transfer will be the court order date.

2. If the assets transfer after decree absolute but on a court order that was made before the decree absolute, then the date of transfer will be the decree absolute date.

3. If the assets transfer after the decree absolute and on a court order that is also made after the decree absolute, then the date of transfer will be the court order date.

It is vital to keep a record of the dates of transfer and whether the fall pre or post the tax year end. As with normal self-assessment filing deadlines, CGT tax returns are due by the 31st January following the year of the asset ‘disposal’.

However, there is now an additional anomaly for UK residential property and land:

- UK residents – For UK tax residents any gains on property or land have to be reported and any tax due paid within 30 days of receiving the gain. An important thing to note here is that a 30 day CGT tax return is only required if there is tax due.

- Non-UK residents – For non-UK tax residents, then it does not matter if tax is due or not, currently a 30 day CGT tax return has to be filed for the sale or transfer of property. Under the annual self-assessment return an individual can then make any adjustments* to that calculation.

*Please bear in mind that this is still a new process for HMRC, and generally speaking any adjustments may take some time to come through.

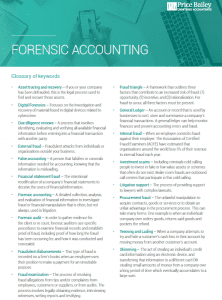

Forensic accounting glossary

You can find our comprehensive glossary for forensic accountancy terms here.

CGT Reliefs

- UK property 2015 / 2019 uplift – From 6 April 2015, non-resident owners of UK residential property have been within the scope of CGT. However, owners of non-residential UK property and land only came into scope on 6 April 2019 for CGT. Therefore, depending on the nature and residency of the property, only gains arising after April 2015 or April 2019 will need to be brought within the scope of UK CGT for non-resident individuals. In divorce proceedings, often this provides a good tax saving because property prices are likely to have increased and therefore, any gain pre-April 2015 or 2019 will be out of charge. There is however the option for different calculations if it is more beneficial for the tax payer.

- Hold-over Relief – Hold-over relief is an asset relief that means the person transferring or gifting the assets does not pay any CGT in certain circumstances (i.e, if a business asset or if IHT is also due). The transfer to the recipient will be liable for CGT when they subsequently sell or dispose of the assets (as they have effectively held over the gain). However, on divorce, currently HMRC’s view is that hold-over will not be allowable as it will be deemed consideration on a court order equal to the market value of the assets being transferred.

- Principal Private Residence relief (PPR) – PPR is available on the disposal of an individual’s main home in the UK which means any gain from the disposal is exempt from CGT. The PPR overriding principle applies to where there has been actual household occupation, this exempts the entire time of occupation. Therefore at the time of divorce if still occupied CGT should not be due on the main house. Please note other deemed periods are also admissible e.g. the final 9 months of marriage which can be useful. Under the PPR rules, tax payers can elect which home is their main home (if owners of more than one property); this rule still applies in divorce.

In addition a period of absence can be extended if the transfer is to the former spouse the below conditions are met:

- The transfer is made under an agreement between spouses in connection with their divorce; and

o Throughout the period from the spouse leaving the property to its disposal, it continues to be the only or main residence of the other spouse; and - The spouse who left the property has not elected for another property to be their main residence for any part of that period. These will include a change to lettings relief which in future will be available only to property owners living in a property while it is rented out.

A key update that came into place from 6 April 2020 is that the spouse that receives the transfer of property will now inherit their spouse’s period of occupation or absence (this is useful if the transfer takes place in the year after separation).

We have provided below a couple of examples of how this works in practice:

| Example 1 – transfer in year of separation

• October 2012 – A & B marry and buy a property together. The value of the property for B = Transfer at No Gain No Loss. |

Example 2 – transfer after year of separation

• October 2012 – A & B marry and buy a property together. The value of the property for B = 50% original base cost and full occupation relief |

A note on residency and domicile…

Residency

Whether either of the parties in the divorce are UK tax resident or not can make a significant difference to the treatment and filing requirements in transfers of assets, residential property or land.

PPR – Individuals are eligible for PPR on their only or main residence. If a spouse is a non-UK tax resident but owns property and/or land in the UK that they plan to dispose of in the course of the divorce, then the individual must meet the ’90-day rule’ in order to qualify for PPR. This rule denotes that the individual has to have spent at least 90 midnights in that property in that tax year in order to qualify. If you are unsure if you meet the 90-day rule then please speak to a tax advisor who will be able to appropriately advise on your particular circumstances.

Domicile

Similarly to residency, if an individual is not UK domiciled then some of the CGT treatments and reliefs become more complicated.

Non-domiciled individuals who are UK tax residents can still possibly arrange their affairs in a tax efficient manner. However, the key thing here is if in the process of divorce assets are being transferred by any non-domiciled individuals, then it is important that planning is done (care needs to be taken to ensure the remittance rules are observed). Another aspect worth considering is to discuss if any indemnities can be put in place.

The rules surrounding residency and domicile with regard to tax treatments in divorce are multi-faceted and will vary by individual’s specific circumstances, therefore it is always prudent to seek professional tax advice to ensure the divorce is managed in the most tax efficient manner.

If you would like to speak to one of our advisors, please contact the team using the form below.

Other tax considerations

- Inheritance tax (IHT) – Firstly, IHT in terms of transfers is somewhat similar to income tax in that individuals need to be mindful of any consequences on IHT as they may be increasing their chargeable estate for IHT in making certain transfers; a tax advisor will be able to advise on this. This is particularly important for non-UK domiciled individuals bringing assets into the IHT net by transferring them to a spouse who is UK domiciled.

- Secondly, regarding chargeable life time transfers, if a transfer of assets is made in the contemplation of divorce then there is no IHT due on the basis that there is no gratuitous benefit. If for whatever reason this did not apply then the transfer would still be a Potential Exempt Transfer (PET); provided the individual transferring the asset lives for 7 years after transfer, then no IHT in life will be due because it is individual to individual. However, if either of the spouses is a non-UK tax resident then it is advised to pay close attention to the legislation in the spouse’s jurisdictions to make sure that IHT planning is complementary between jurisdictions.

- Stamp Duty Land Tax (SDLT) – SDLT does not usually need to be worried about in contemplation of divorce by either spouse at any time during the divorce. However, if a spouse has elected for PPR on another property other than the main home then CGT and SDLT may not match if the elected home for CGT purposes differ to that for SDLT.

This article was written by Nikita Cooper, Tax Director at Price Bailey, specialising in personal tax for high net worth individuals, trusts and family offices. Nikita works closely with Denise Cullum our Forensic Accounting lead to support and advise clients through the divorce process to make it as stress free as possible for all parties.

If you are thinking about, or currently in the process of divorce from your spouse and would like further advice on the process or how to minimise your tax position, please contact the team using the form below.

We always recommend that you seek advice from a suitably qualified adviser before taking any action. The information in this article only serves as a guide and no responsibility for loss occasioned by any person acting or refraining from action as a result of this material can be accepted by the authors or the firm.

Sign up to receive exclusive business insights

Join our community of industry leaders and receive exclusive reports, early event access, and expert advice to stay ahead – all delivered straight to your inbox.

Have a question about this post? Ask our team...

We can help

Contact us today to find out more about how we can help you