M&A explained - The importance of working capital in pricing mechanisms

Completion mechanisms are used in M&A deals in order to determine the final price that a buyer will pay in the acquisition of the shares of a company. There are two commonly used mechanisms in M&A transactions: Completion Accounts and Locked Box.

The outcomes for each can vary significantly but, as Phil Sharpe discusses below, the key to achieving optimal value and a mutually beneficial outcome for the buyer and seller lies in first ensuring the inputs to either mechanism are true, fair and accurate.

When someone offers to buy a business they will usually value it on the basis of an Enterprise Value which assumes that the acquisition will be:

- on a cash-free and debt-free basis, and

- subject to having the normal level of working capital.

While Enterprise Value provides the value of the business (or enterprise), it does not inform the seller of what they will receive in terms of proceeds from the sale, nor what the buyer will need to invest in order to maintain growth. Therefore, most deals also involve a number of adjustments to the purchase price to achieve this. These adjustments are predominantly in relation to cash, debt, and working capital levels. They are a vital part of pricing negotiations and can result in a significant impact on the price.

The process of making these adjustments is what is known as an Enterprise Value to Equity Value bridge, as the resulting figure (the Equity Value) will provide both buyer and seller and with a truer reflection of what consideration will actually be paid/received on completion.

Adjustments to Enterprise Value

Surplus cash and normal working capital

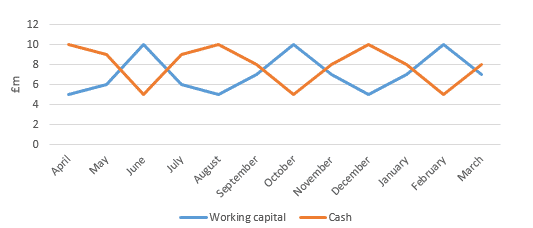

Given that the value of cash is being added to the enterprise value in getting to price paid, the buyer will want to ensure any cash being paid for is surplus to trading requirements, and that cash has not been artificially increased through short term working capital management. In other words, ensuring they don’t walk in on day one and find a requirement to pay creditors that should have already been paid in the normal course of business, or that the stock room is empty. To ensure this is not the case, surplus cash needs to be assessed with reference to normal levels of working capital. However, the challenge is that cash and working capital vary on a daily basis in normal trading conditions which means the assessment of normal working capital, and thus surplus cash, is the subject of significant debate.

The relationship between cash and working capital

Working capital is calculated as Current assets – Current liabilities. As such, working capital is classified as an Asset and when asset value increases this typically results in a reduction in cash as the business has had to spend money on the asset, and vice versa.

Why this is important to valuation? Because a company’s value relies significantly on its future potential, in particular, its future cash flows. Therefore, changes in working capital provide an idea of the extent to which a company’s cash flows will differ from net income.

What is the “normal” level of working capital of a business?

Working capital is the amount of operating capital that a business requires in the day-to-day running of the business. Working capital needs can vary throughout the year for businesses in growth, decline, or with seasonality. The key is in enabling a buyer to understand what a normal amount of working capital operating in the business needs to be, in order to appropriately determine an offer to acquire the business.

Calculating normalised working capital requires commercial judgement and whilst there are many ways it can be calculated, often it is measured by looking back 12 months to iron out any seasonality. However, in a growing business it may be more appropriate to look at a shorter or more recent period, or in fact to look forward at the future 12 months especially if the price is based on the further performance of the business. There will also be a big variation between the average working capital and peak. Not to mention that there needs to be agreement on what is cash/debt and working capital and consideration of any ‘one-off’ items that should be excluded, or a variation to trading practices that may affect the assessment. Overall the methodology chosen for calculating normal working capital will differ depending on assessing the preferred position (as the buyer or seller) and creating an argument why one methodology is the more appropriate than another. The decision on how to calculate normalised working capital, however, should not be underestimated as both the timing and content will not only impact on pricing but will also need to be documented in both due diligence and the SPA.

Defining cash, debt and working capital

This should be easy, right? Cash is money in the bank, debt is money owed to the bank and working capital is the sum of stock and trading debtors and creditors. However, there are significant ‘grey areas’ when it comes to categorising items as either cash (or cash-like) or debt (or debt-like), and reaching agreement on these between buyer and seller can take some time. Examples that create confusion or contention include:

- Rent deposits – cash in the bank, but required to secure rented property is not cash that can be freely paid out and thus required for working capital

- Taxes – Corporation Tax is viewed as debt-like whereas PAYE and VAT are working capital items

- Deferred Income – is often argued as both debt and working capital. The view on which wins the toss often depends on whether on the buy or sell side of the table.

How do Completion Accounts and Locked Box mechanisms compare?

The principles of agreeing a “normal” level of working capital, and as a consequence the calculation of surplus cash, applies to both Completion Accounts and Locked Box mechanisms. However, the timing of the calculations differ. Let’s look at each of them in turn:

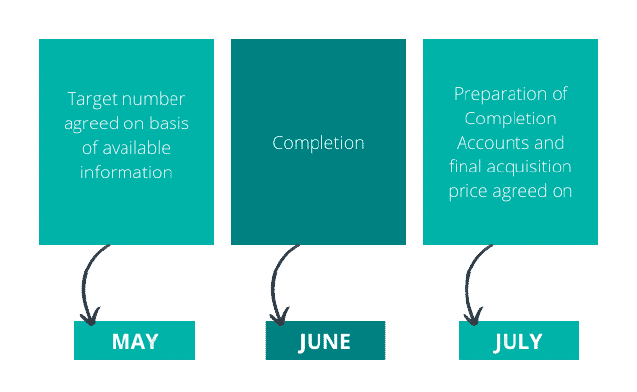

Completion Accounts

Completion Accounts operate on the basis of price adjustments made depending on the financial position of the business as assessed in the accounts on the day of completion. In practice, both buyer and seller calculate and agree on the normal level of working capital for the business prior to completion; what is called the ‘target net working capital’ for the acquisition price that is used in the Share Purchase Agreement (SPA).

After the deal closes, typically the buyer will compile the completion accounts showing the assets and liabilities of the business (including working capital, cash and debt) at the completion date.

There will then be an adjustment to the price for cash and debt in the business, and to the extent that the actual level of working capital is higher or lower than the agreed target number. This may mean that additional cash will flow to the sellers or the sellers being required to repay any shortfall. This is to ensure that whilst the sellers benefit from any surplus cash, the buyers have the required level of working capital in the business to cover normal operations at the point of acquisition.

Accounting policies

The accounting policies and practices that are applied when drawing up Completion Accounts is an area of significant debate. Typically, the Completion Accounts on a transaction are prepared on a basis that is consistent with the target’s last annual accounts, and where any differences should occur (whether that’s for particular treatments or where the policies and practices used differ from the accounting standards governing those accounts), express wording to that effect should be detailed in the SPA.

In the UK, there will typically be a 3-step waterfall process to determine the specified treatments:

- Specific policies – there will typically be a list of specific policies such as provisions for old stock or doubtful debt which may not have been applied consistently in the past,

- Historical accounting practices – whatever is not covered by specific policies will be subject to historical accounting practice,

- Finally, anything not covered by specific or historic policies will be referred to UK GAAP, US GAAP or international accounting standards, whichever is most relevant.

On occasion, sellers will try to include all the historical practices in the specific policies – this is not necessary and only captures in lots of detail what is already covered as the default position. However, there is a balance to be had as if certain specific policies aren’t in place, the buyers will calculate the historic numbers based on documented policies to ensure consistency when calculating the target number. The specific policies should, therefore, only be used for different treatments or provisions that haven’t been used historically, in order to create a true reflection of fair value.

A Completion Accounts deal can create uncertainty as the sellers will not know what they will receive for their shares until after the sale date. After signing the SPA, the buyer is in control of the business and will draw up the Completion Accounts that will determine the overall price paid. Depending on the nature of the buyers, or the nature of the relationship between buyer and seller, this can put the seller at risk of the buyer being more aggressive on the accounting policy applications and judgements taken when drawing up the Completion Accounts.

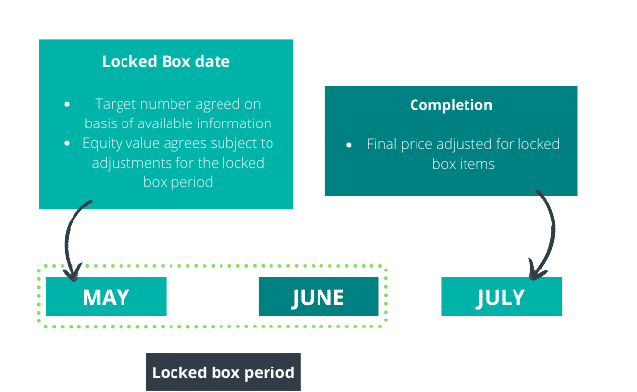

Locked Box mechanism

In a Locked Box scenario, a guide price is agreed prior to signing based on the balance sheet prepared at the Locked Box date (which could be several months prior to completion). On completion, a final equity value adjustment is made based on performance between the Locked Box date and completion, in order to determine the final price paid. This adjustment is made to account for the growth in the equity value of the business between the Locked Box date and the Completion date, i.e. the retained net profit. A Locked Box mechanism is often simpler than completion accounts as 1) they avoid time spent post-signing on completion processes and, 2) having an idea of price prior to completion gives all parties greater certainty.

The term ‘Locked Box’ refers to the fact that from the Locked Box date to completion of the sale (the Locked Box Period), value does not leave the business. Movements between cash and working capital continue to take place but there is need to measure them at the completion date as, overall, such movements cancel out. Vendors would need to confirm there had been no leakage of value from the business during the Locked Box Period, such as dividends or exceptional bonuses, and in there event there was, they would need to be adjusted for in the final price. As long as the purchaser is getting the cash and the working capital, then any movement between the two doesn’t matter, as ultimately it does not make any difference to the overall value.

Is there a preference?

Locked Box and Completion Accounts are, broadly speaking, quite similar. The Locked Box provides certainty on the final price at the date of signing, whereas the price still moves post deal under the Completion Accounts mechanism. This is often preferred by sellers where they have a large shareholder base and need to be able to communicate certainty on the deal value to get shareholder approval. However, to get certainty they may need to give up some value. In contrast, Completion Accounts may be the preference for a buyer as they will know that they will only be paying for what they get, and they will have the ability to scrutinise working capital in more detail when they are in control of the business.

Ultimately the preference will depend on the attitude of both parties. There are a number of factors that can impact the preference and no one circumstance is the same. Nevertheless, obtaining the most equitable outcome for both parties will rely predominantly on the quality and accuracy of the inputs that go into determining the price. Getting that right will make the difference between a quick, harmonious and mutually beneficial outcome, and a prolonged (at times, unpleasant) process that costs more time, money and headache.

This article was written by Phil Sharpe, a partner in the SCF team. If you would like support or advice on the sale of your business, or anything else mentioned in this article, then you can contact Phil using the form below.

We always recommend that you seek advice from a suitably qualified adviser before taking any action. The information in this article only serves as a guide and no responsibility for loss occasioned by any person acting or refraining from action as a result of this material can be accepted by the authors or the firm.

Have a question about this post? Ask our team…

Sign up to receive exclusive business insights

Join our community of industry leaders and receive exclusive reports, early event access, and expert advice to stay ahead – all delivered straight to your inbox.

We can help

Contact us today to find out more about how we can help you